Today, I’m pleased to welcome a teacher and friend, Renee LaTulippe. I have known Renee for a couple years, but it feels like even longer through her online videos. [Note to readers: If you have questions on writing in verse, check out Renee LaTulippe's website for answers to all your nagging questions on meter and more.]

Let 's get right to it!

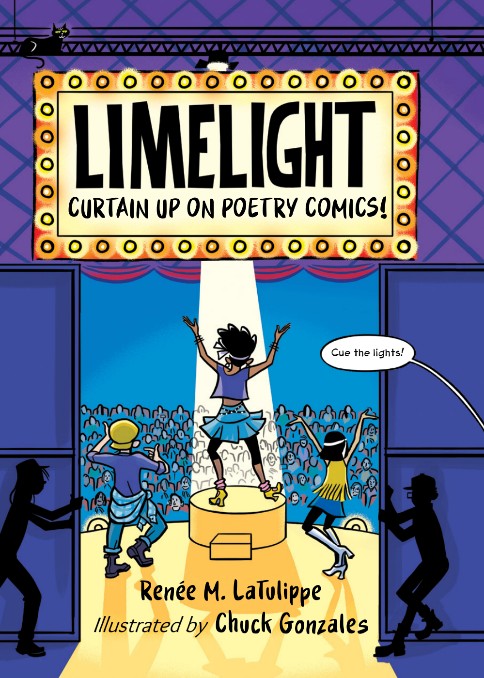

TKJ: Renee, I am so excited about your forthcoming book Limelight: Curtain Up On Poetry Comics! It's truly unique with bits and bobs of comic book, graphic novel, and poetry collection. The subtitle says it all: curtain up on poetry comics! Did you envision a comic format from Limelight's inception? Why is the format important?

RL: Thanks for having me, Tracey!

I definitely did not envision a comic format for Limelight! To be honest, I wasn’t quite sure what I had created with this manuscript, or for what age group, so it was hard for me to imagine what shape it would take. Luckily, I had a visionary editor—Yolanda Scott—who did a lot of that noodling for me and eventually suggested the poetry comics format. Once that idea was out there, I had a much clearer vision of what I wanted—and it was very painterly, to be frank. After exploring that rather austere path a bit, Yolanda suggested this more kid-friendly graphic novel style. I admit it took me a minute to come around to the idea, but soon enough I realized she was absolutely right!

In fact, this format helped define the audience for the book, and even the book’s purpose and place became so much clearer to me. Making poetry engaging and accessible and simply interesting to a wide range of kids still seems like a tall order, and this format helped do all those things. I could not be more thrilled with the whole process and how Yolanda’s vision—and Chuck Gonzales’s illustrations—brought the manuscript to life.

TKJ: How interesting that the art style helped define the purpose of the book after the text was written!

You've often mentioned Lee Bennett Hopkins as a friend and mentor, and in your dedication, you say that he "pushed you onto the stage.” Please tell us the backstory! [Note to readers: Check out Lee and Renee's series on the History of American Children's Poets.

RL: Ah, Lee—how I miss him! And how sad I am that he never saw Limelight come to fruition. The backstory is simply that, in 2012, I asked if he’d be willing to do a video interview for my NoWaterRiver.com poetry blog. He said yes and we just hit it off! Over the years we created a series of videos covering the NCTE Poetry Award winners, and then an unfinished series on the history of children’s poetry. While recording these videos, we’d go off on long tangents to chat about poetry and poets and theater and publishing, and he’d tell me stories of his childhood and his long poetic career. He was very special.

Lee and I shared a love of musical theater, so when I began writing Limelight in 2015, Lee was right there to offer his mentorship, commenting on each poem and pushing me to do better, always better. He was such a champion of this book, and of me. It was during this time that he referred me to his agent, who eventually signed me and sold Limelight three months later. It was my first book sold, the second to come out. Lee’s influence and encouragement played a big role in getting my work seen by a wider audience on the poetry stage!

TKJ: Lee sounds like a wonderful person. How lovely that he was able to have a hand in bringing Limelight into the limelight!

I enjoyed learning things only a theater person would know from reading Limelight – such as the reincarnations of a costume. Please tell us about some of your theater experiences. Did you need to conduct any research or consult with other experts to write this book or did it grow primarily from your life experiences?

RL: I have a long and deeply un-famous history on and around the stage, so I’ve had at least some experience in every aspect of theater, from lights, sound, scenery, costumes, and box office to acting, producing, directing, and teaching improv. While I do have a BFA in theater, most of the poems in Limelight were inspired by my time working at my hometown summer stock theater, Fort Salem Theater, in the mid-1980s. This book has a double dedication, and the other is to Quentin Beaver, who was the producer at Fort Salem. That theater was my training ground, where I worked nonstop for little pay and loved every second of it. We’d rehearse our next musical during the day, perform the current one at night, and in between I’d be running around building props or painting scenery or helping with costumes (and yes, over the years I saw my costume from Showboat repurposed for Oklahoma! and then Brigadoon, and so on). So other than looking up a few technical terms, the collection grew from my direct experiences.

It’s the kind of formative experience I’d wish on every young person: a period of full immersion in whatever your passion may be.

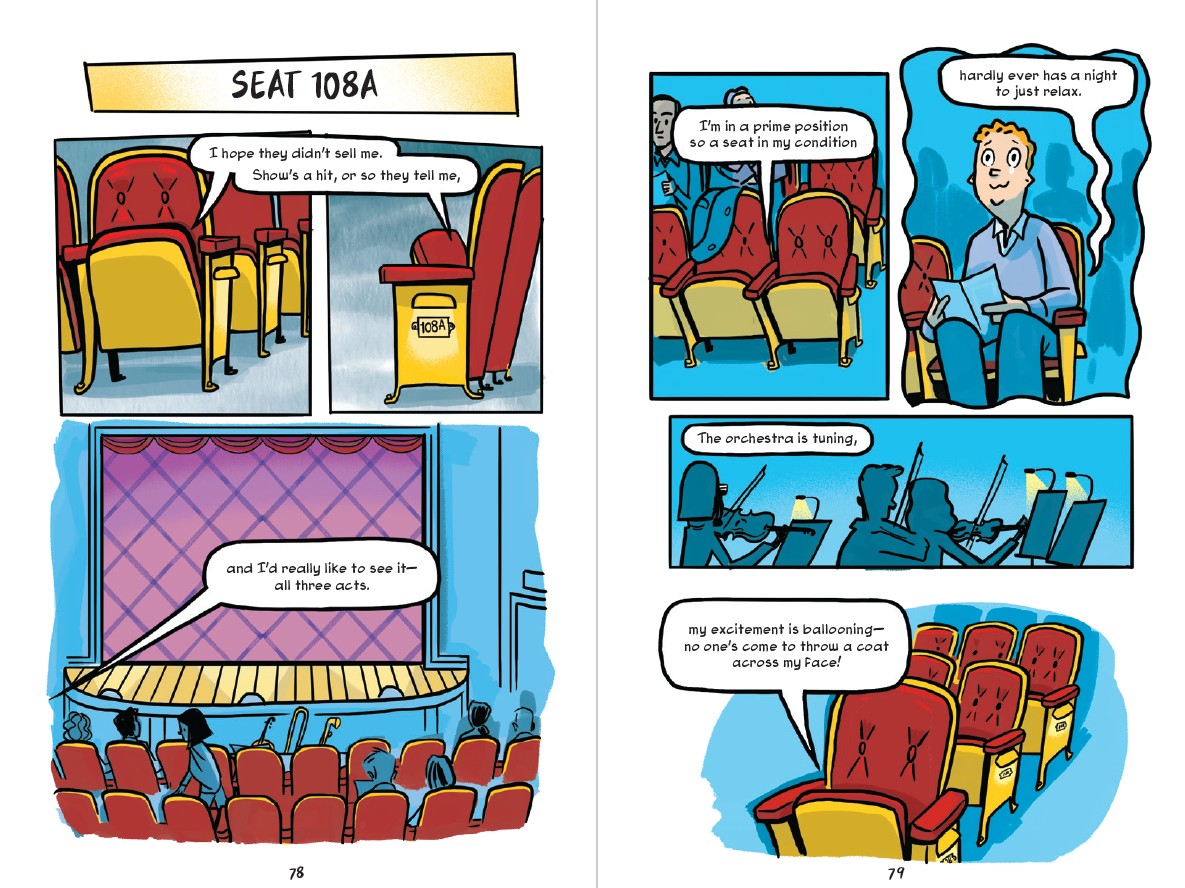

TKJ: "Seat 108A" is hilarious. I never thought I would empathize with a theater seat! Could you explain what a mask poem is and why it is the ideal structure for this book? Do you have a method for "getting into the mind" of an inanimate object?

RL: Ha! Thank you! It’s one of my favorites in the collection, so I’m glad you found it amusing. In a mask poem, you write in the voice and from the POV of an object, animal, or idea. So you, the poet, must use the age-old theater technique of the “Magic If,” which is simply an actor asking herself "What would I do if I were in my character’s situation?" The Magic If helps an actor use their imagination to connect with their character, and creates exactly what you mentioned: empathy. In writing a mask poem, the Magic If helps me imagine what I’d do and how I’d feel if I were a piano with a broken string, a seat who dreams of seeing the show, a heavy curtain who is past his prime.

I did not have to think twice about using mask poems for Limelight. Besides being my favorite kind of poem to write, mask poems are really little monologues, aren’t they? I have a specific voice in my head for every character in the book (my favorite being the rehearsal piano from Brooklyn), and I listened to each voice while I was writing its poem/monologue. Hearing the character’s voice is a great help in developing the right poetic structures, phrasing, cadences, rhythms, and word choices, which all work together to help the reader feel empathy for the object. For me, they cease to be objects and become living, emotional beings.

Side note: It’s funny that you ask if I have “a method” for getting into the mind of an object. The Magic If actually comes from the Stanislavsky technique of acting—a technique that is famously referred to as “method acting.” While I was not a method actor, the Magic If is a wonderful tool for freeing the imagination, similar to the “What If?” that writers use to generate ideas.

TKJ: I stumbled upon your video of the poem "Betty's Tap Shoes." Are those your tootsies tapping away to the clever rhyme of "middle" and "paradiddle?"

RL: Sadly, no. While I ever so briefly took tap lessons as a theater undergrad, my salad days were too salad-y to allow me to keep paying for them. Haha. Alas, I never learned how to do a funky paradiddle. The toes and the talent in the video belong to my long-ago fellow theater student and friend Jessica Rein Froehlich. I sent her the voiceover and she worked her magic. (Extra shoutout to Jessica in her role as artistic director of the Minneapolis company Unlabeled Theater Company, which produces inclusive theatre performances featuring theatre artists with cognitive and/or physical disabilities or who are neurodivergent.)

TKJ: Thank you for sharing information on Jessica’s important work!

There is often a wall between the author and illustrator in publishing, but in Limelight, the text and illustrations tightly intertwine. Could you talk about the process of creating the book and your level of interaction with the illustrator, Chuck Gonzales? When did the idea of the "Music Review: Decades” motif arise?

RL: Again, I must thank my editor for her vision here! While I did not directly interact with the illustrator, Yolanda kept me in the loop and solicited my thoughts on every aspect of the book. We discussed how to create a visual story around the poems, and we eventually hit on the idea of putting together a middle school musical. As a way to give direction to the illustrator and create consistency across the collection, she asked me to write an outline of a musical, complete with characters, scenes, song titles, and dance numbers … so I did, and had way too much fun with that! She then took my overblown ideas and distilled them into the more manageable idea of a musical review that would take the same cast of characters through the process of producing a show from soup to nuts.

I consider myself exceedingly lucky to have been asked to contribute so much to the illustration process from initial sketches to final product. Perhaps due to my background in directing/producing, I do tend to write a LOT of detailed notes on illos, and it was a real gift to have my ideas and concerns welcomed, listened to, and incorporated into the book.

TKJ: The theater metaphor is incredibly well-executed. Backstage (a clever name for the back matter) includes wonderful resources, so we can nerd out on poetic forms. Echo Verse was new to me, but I immediately loved it! Were there any forms that you included that were newish to you?

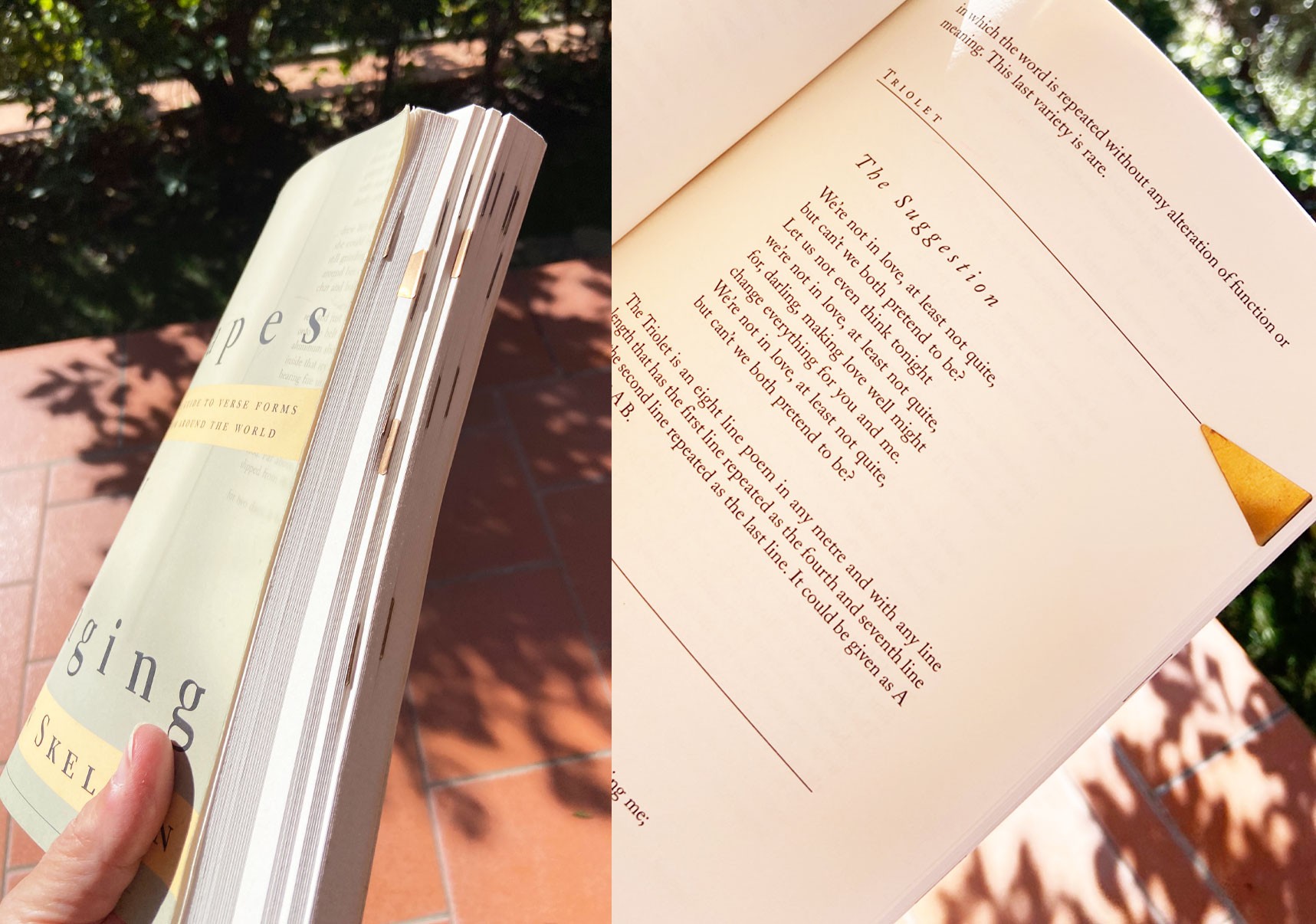

RL: So many forms! For this collection, I referred to Robin Skelton’s The Shapes of Our Singing, a marvelous guide to world verse forms. I wanted to challenge myself to discover and write new-to-me forms, and I spent hours poring over this book, looking for just the right structure for each character. (As you can see, the bookmarks I placed on possible forms are still there for posterity. :D )

Forms I’d never written were the triolet, reverso (learned from the works of Marilyn Singer), echo verse, roundel, pregunta, and poem within a poem (inspired by the verse novels of Ellen Hopkins). While my first love is actually free verse, trying new forms really loosened up my imagination and creativity.

Forms I’d never written were the triolet, reverso (learned from the works of Marilyn Singer), echo verse, roundel, pregunta, and poem within a poem (inspired by the verse novels of Ellen Hopkins). While my first love is actually free verse, trying new forms really loosened up my imagination and creativity.

TKJ: I am so glad that you included the text of each poem later in the book. The first half of the book allows the reader to relax into the story. The second half allows the reader to savor the samplings from your smorgasbord of poem forms. Not to mix metaphors, but deciphering poetic forms also can be like trying to comb tangled hair – forms sometimes overlap and twist around each other. Were any poems particularly confounding to write?

RL: Repetitive forms like the pantoum (“Curtain’s Lament”) and the triolet are always a challenge. The triolets for the pit orchestra were a particular brain squeeze, but they allowed me to really play with the sounds of the instruments. And the reverso is frustrating indeed!

The most confounding poem, though, is arguably the “simplest” in the collection: “Applause Bursts On the Scene.” I just could not figure out how to write it, and I still have my emails to Lee to prove it. In one I wrote, “In an ongoing effort to avoid writing ‘Applause,’ I have revised the back matter. What do you think?” (Note: Lee did not give a hoot about back matter.) Hahaha.

The original poem was a dodoitsu, a four-line Japanese form with a syllable count of 7 7 7 5. I’m not a big fan of writing syllabic verse, but I liked the idea of keeping it short and sweet. I struggled with that poem for a good month, squashing it into various forms and having Lee send me back to the drawing board before realizing that my applause needed to be uncaged—so I wrote it in free verse.

The easiest to write, not to mention tons of fun, was the epistle for the piano. I love writing dialogue, and that one just flowed out because the piano’s voice was so strong in my head. I have a real soft spot for that guy!

TKJ: It is amazing how effortless the finished product appears! For us writers who struggle with finding the right word, meter, or subject it is heartening to understand the effort that went into these wonderful poems.

I understand that you speak fluent Italian. Does speaking Italian influence your writing in English? If so, in what way?

RL: If by fluent you mean “speaks in a completely understandable way albeit with sad grammar,” then yes, I am fluent in Italian. Perhaps a more Italian cadence or turn of phrase will creep in here and there, but otherwise I don’t think the language has had much influence on my writing.

Speaking is another matter, and Italian sentence construction has definitely creeped into my spoken English, so that I might utter something like “It is beautiful the weather today.” I will also randomly forget simple English words like “yellow” or “hat.” Luckily writing allows me more time to put two thoughts together coherently!

TKJ: How long did it take for Limelight to go from a twinkle in your imagination to the glowing book that is now available for preorder? Were there any unexpected challenges in the journey of creating this book?

RL: Isn’t everything a challenge in publishing? Seriously, though, it only took a decade. I completed the manuscript in summer 2015, then I got an agent and sold it pretty much simultaneously in late 2017. So the biggest hurdle has been waiting eight years for it to come out. And just as we were finally getting underway a couple of years ago, our first illustrator (the painterly one) backed out, so that was a whole thing. But the various delays were worth it in the end because the book ended up being exactly what it was meant to be!

TKJ: Thank you so much for sharing your insights with us, Renee! We wish you great success with the launch of Limelight! Do you have any upcoming plans in the works?

RL: Right now I am hyper-focused on writing a story-based curriculum called Hit the Road Geography for my own company, Storylark Road. I’ve been writing for the educational market since 2008 and am thrilled to have launched Storylark with a long-time colleague.

In the traditional market, I have a free verse nonfiction picture book coming out with Creative Editions in 2027-ish, and I’m about to start shopping around my YA verse novel, which is also theater related. All appendages crossed for that!

Thank you for giving this space to Limelight, Tracey. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate it!

TK: Thank you for sharing your amazing insights, Renee! Best wishes for you and your readers!

Limelight will be available on October 28, 2025 and can be preordered here.

Thank you to our Poetry Friday host, Amy Ludwig Vanderwater. Please head over to The Poem Farm for this week's roundup!